In the current arena of veterinary practice sales, it is impossible to ignore the intense interest in practice consolidation by corporate entities, but it should be noted that this trend is not brand new. Corporations have owned veterinary practices for over 30 years, tracing back to when VCA Animal Hospitals first bought a small animal practice in 1987. Other corporate entities eventually caught on, as VCA’s success led to the formation of several regional and national chains, such as Banfield, NVA, and VetCor. Analysts now place the number of corporate veterinary practice groups at over 40 and growing. In just the last three years, though, the landscape has drastically changed. Multi-billion-dollar deals are not unheard of, such as Mars, Inc. purchasing VCA for $7.7 billion in 2017, or the very recent purchase of Compassion First Pet Hospitals by JAB, Ltd. for $1.22 billion. As another factor to consider, private equity firms, which see veterinary practices as relatively safe investments, are now funding many of the acquisitions by corporate groups.

According to the 2017 AVMA Report on the Market for Veterinary Services, the number of small animal veterinary practices in the USA ranges from 28,000 to 32,000. Brakke Consulting estimated in 2017 that about 3,500 practices were owned by corporations. Companies own roughly 10 percent of all general companion animal practices and 40 to 50 percent of all referral practices. John Volk, an analyst with Brakke, explains, “What happens is a larger company comes in and buys up the smaller companies and builds a bigger firm.” This is called “roll-up,” a common business strategy applied to many industries made up of multiple, small, independently-owned companies, and has become the new model for veterinary practice sales.

Contrast that with the traditional model for practice sales, in which an owner sells to one of his or her associate veterinarians, likely groomed from day one to eventually take the reins, or where the owner might sell the practice to another veterinarian who was not employed by that practice. Either way, that is no longer the case for most small animal practices. Owners have now found themselves in a seller’s market, where large corporations will pay top dollar for a thriving practice, with corporate windfall offers typically vastly exceeding those of any associate or other private interest buyers. A windfall is defined as “a piece of unexpected good fortune, typically one that involves receiving a large amount of money,” with synonyms being a bonanza or jackpot, or pennies from heaven. Corporations, now routinely providing such payouts to sellers in nearly unbelievable but carefully calculated offers, are doing so for the following reason: a corporation is ready and able to take a hit on a practice’s purchase price as long as its long-term profitability and growth prospects appear satisfactory. Many veterinarians have made a fortune out of their practices this way, often making two to three times what they would have made by selling to an associate. It can be hard to refuse a corporate buyout when the seller has offered such terms. Plus, a corporation can buy almost immediately, typically with a cashier’s check for the full purchase price in pocket, versus associates for whom the seller will very likely have to finance some or all of the purchase themselves, and for a fraction of the corporate purchase price.

Now we return to the subject of associate veterinarians. Although circumstances differ in each sale, one cannot deny that a significant reason that corporations are offering large cash windfalls is often the presence of the associate veterinarians. Corporations want to buy thriving practices that are operational from day one of purchase, with veterinary and support staff in place. A veterinary practice does not exist without veterinarians, and buyers generally have no intention of replacing associates. Furthermore, associate veterinarians usually do not wish to leave when practice ownership changes hands.

Here’s another reason why associate veterinarians are typically off the playing field. The typical associate sometimes cannot afford to be a practice owner. This often stems from the mass amount of veterinary student debt that they have accumulated and may be paying off for many years. According to results from the AVMA’s 2015 annual survey of senior veterinary students, of those students who graduated from the 28 US colleges and schools of veterinary medicine, 89% had educational debt at the time of graduation, with average debt for veterinary students being $142,394. Approximately 68% of the 2015 graduates had debt between $50,000 and $221,000, with 5% having debt greater than $300,000.

These are staggering figures, but what may be even more disturbing is the discrepancy in associate veterinary wage increases versus their debt. The current debt load of veterinarians is rising by $4,900 per year while average salaries are only rising by $700 per year. In 2017, $76,130 was the average salary for a veterinarian, while the mean debt was $141,000. This rising debt-to-income level is unsustainable and is one of the major factors making this profession less attractive than in the past. In fact, a recent Merck veterinary wellbeing study showed that only 41% of veterinarians overall and only 24% of veterinarians younger than 34 years old would recommend pursuing a career in veterinary medicine, citing that student debt coupled with low income was the top concern contributing to emotional stress. Furthermore, between standard and extended loan repayment plans, veterinarians on the average spend 15 to 20 years paying off their student debt. Hence, it is increasingly difficult for an associate to qualify for lending from a bank in order to compete with a corporation on a purchase price, with very little chance for the associate to be able to match the cash windfall offered by a corporation.

In this current climate, it is easy to see why so many practices are sold to corporations. But, while the seller receives the cash windfall for the sale, the remaining associates typically receive no supplementary compensation of any sort—the same associates who often helped to build the practice and who are integral for its revenue, often contributing 30% or more to the overall practice gross. This begs the question, then: Is it not fair for the associate veterinarians to share the windfall?

As stated, the corporation is buying a thriving practice, one not possible to operate at a similar capacity in the absence of associates. So, as an industry, should we not be sharing some of the profit from sales with the associates whom are so integral to the sale itself? Upon practice sale closure, associates are terminated by the original employer and then typically rehired by the new owner. An argument can be made that the associate accordingly deserves a new signing bonus, as they are technically a new hire and should be incentivized towards employment.

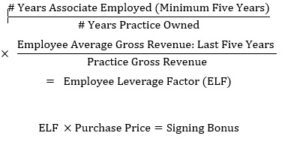

In order to decide upon an appropriate value for an associate’s hypothetical signing bonus offer, one could develop a calculation based on actual numbers. The prototype calculation herein requires basic information regarding time and revenue, including the following factors: the number of years the associate has worked for the practice (a minimum of five years of employment), the number of years the seller has owned the practice, the associate’s average gross revenue over the last five years, and the practice’s current gross revenue. With this information, we establish the Employee Leverage Factor (ELF), a figure which, when applied to the purchase price, yields the appropriate signing bonus. The calculation is as follows:

If, for example, an employee has been working for ten years at a practice that has been under current ownership for 35 years, and over those last ten years the employee has been bringing in an average of $700k while the practice brings in $2.1M, the equation would follow as such:

If the practice sold for $4.5M:

In this example, the seller still nets $3,620,000.00, cash in hand, over 1.7 times the gross of the practice.

Thus, we have established a fair and reproducible calculation of an offer that reflects the associate’s contribution to the “windfall” price received by the seller. The calculation should only apply in the case of a major windfall, in our estimates at least 1.5 x gross revenue and all cash. The calculation could be adjusted as the seller sees fit but, as it stands, it is a fair representation of contribution. It is based on the associate’s average gross revenue over five years, and also only applies if the associate has worked at least five years. So, if they have worked 5.5 years, but did not gross nearly as much in the first two years, those initial lower numbers are factored in. For example, if that associate had an average gross of $400k:

If the associate had worked for ten years, as in the first example, it is justified that the signing bonus offer is greater because that associate likely helped significantly more in building the practice, contributed more to the practice’s gross revenue, and thus made the package more appealing to the corporate buyer.

But, should there be a factor that weighs the windfall itself? The previous examples are based on a flat payout in a high windfall. But, if the windfall is of a lesser amount, then the associate’s share should be weighted as less, accordingly. If we use a maximum sale price as 3x the practice gross, we can incorporate a factor that includes the actual sale price over max gross, thus weighing the windfall.

= Weighted Share of the Windfall

x is the multiple over gross; is the Weighted Windfall Factor, or WWF.

Using the previous example with the ten-year associate whose average gross was $700k at a 2.1M grossing practice (35 years in business):

If the practice now only sold for $3.15M (1.5 x gross), = WWF

The seller still nets $3,000,375.00 after receiving a lesser windfall for the sale.

A large share of the windfall could be enough to make the associate take the money and run, leaving the practice high and dry. To offset those odds, the signing bonus could be offered instead as a retention bonus, with part of the sum paid up front to the associate and the remainder paid over the agreed length of employment. Or, keeping in mind the high amount of student debt that most associates have, the calculated bonus can in whole or partially be assigned towards debt payoff. Thus, sharing the windfall would secure loyalty and stability for the future of both the associate veterinarian and the practice itself, meriting strong consideration.

The signing bonus offer would come out of the purchase price, and hence may not appeal to the seller. But we must remember that the long-term associates who would benefit from this process are the same ones who helped to build the practice to its current capacity, potentially contributed a high percentage to the practice’s gross revenue, and made the package more appealing to the corporate buyer, thus contributing to the windfall itself.

Without such a bonus, the associate otherwise gets nothing out of the deal. In their eyes, their future with the corporation is uncertain. They may have a new or broader non-compete agreement. They may not have wanted to work for a corporation at all. Furthermore, when they inevitably find out the size of the seller’s windfall, they may feel cheated after putting so much time and effort into the practice and getting no reward. This negative outlook may be compounded tremendously if they had otherwise hoped to someday buy or buy into practice ownership, with this disappointment added on top of the debt and stress they are likely already under. We also cannot disregard the real and unfortunate rise in the suicide rate among veterinarians in the face of issues such as emotional stress, debt, and compassion fatigue. That is the world in which the associate veterinarian lives in. We must therefore ask ourselves, is it moral as an industry to not include our associates in the windfall from corporate sales?

While the corporate consolidation trend will inevitably slow down, it is currently encompassing the world of veterinary practice sales, far and wide. As industry leaders, we must bear in mind the circumstances of many of our peers as associate veterinarians and the effects that our decisions to sell to corporate entities may have on them. The concept and application of sharing the windfall via the associate veterinarian signing bonus would secure a high degree of financial and thus psychological stability in the associate. Furthermore, it would create security for the future of the practice itself through the loyalty it instills in the associate, ensuring that they feel appreciated as the assets that they truly are.